December 27, 2017 – Final Post

The Armistice officially ended the fighting on November 11, 1918. Some men stayed on as occupation troops in Europe into 1919, while other St. Louisans stayed in the military into 1920 or even longer. Men trickled home, singly or in small groups, but in the spring of 1919, trains full of servicemen began arriving at Union Station. In May 1918, the city held receptions and a huge parade downtown for those who came home.

About three dozen men from the St. Louis Jewish community gave their lives in the Great War. The Graves Registration Service finally found the remains of Samuel Morganstern in 1926. He had died at the Hills of Chatillon, Ardennes Forest, on October 23, 1918. He was among the last to come home.

The State of Missouri, the city of St. Louis and other communities, as well as congregations, schools and organizations, commemorated the service and sacrifices of those who served. Many of those memorials remain today including Soldiers’ Memorial and the Missouri monument in Cheppy France. Other memorials, like the bronze plaques and trees created by the Gold Star Mothers and placed along Kingshighway, no longer exist in their original form, but are part of newly-created memorials located elsewhere.

Our goal with WWI Wednesday was to bring attention to the many individuals from the St. Louis Jewish community who served during the Great War. We hope that in some small way we have contributed to awareness concerning the US involvement in the war through the actions of these men – and a few women.

Through our research, we gathered information about more than 600 individuals from the community who served in the war, but we know there are others who we did not locate. Thus, if you have information about someone who served in the war who was from the St. Louis Jewish community, please let us know. We’ll be happy to share information we have about them and will gladly add your data to our records. We hope you will continue to remember those who fought in “the war to end all wars.”

December 20, 2017 – Harry E. Lappeman

Harry Lappeman, born in St. Louis in 1893, was the oldest of the six children of Dr. Alfred and Sarah Lappeman. His optometrist father and socially-active mother were well-known in the Jewish community. On draft registration day in June 1917, Harry was living with his parents and working as a medical company receiving clerk. He had, however, already spent four years in the Navy and was “subject to call.”

When recalled to duty, Lappeman found himself on various receiving ships, then the USS President Grant, before finally being assigned to Sub Chaser 263 (SC 263) toward the end of the war. These ships, referred to commonly as “110s” because of their overall length of 110 feet, were relatively new to naval warfare. The SC 263, part of the USS Henley Hunting Group, patrolled the US coastline from Maine to Rhode Island.

Even before the US entered the European War, the Navy realized that submarine warfare required countermeasures. During the summer of 1916, two German submarines had “visited” the US and promptly sank five ships after leaving the coastline. That incident prompted the Navy into action, particularly young Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt. Roosevelt urged the hiring and commissioning of naval architect Albert Loring Swasey to design a vessel worthy of the task. Swasey’s design needed to be small and quickly built. Because steel supplies were already committed for the construction of larger ships, these new sub chasers had to be built of wood – thus leading to their nickname as “the splinter fleet.” These wooden vessels had a 1,000 mile range, perfect for patrolling the coastline especially after the German government declared unrestricted submarine warfare in February 1917. The new sub chasers were meant to detect German submarines via deck-watch, hull-mounted hydrophones, and copper wire trailing antennas. Although the military value of these small submarine chasers is debated even today, these 110s were an effective anti-submarine deterrent and crucial to American peace of mind.

Early on, armament for these small ships consisted of two 3” cannons and two machine guns, but depth charges had to be manually deployed off the stern. The Navy soon realized the hazards of the latter leading to the replacement of one cannon with a Y-shaped depth charge thrower. George Lawley & Son shipyard in Neponset, Massachusetts, built the SC 263, which was commissioned in Boston in February 1918. After the war, this sub chaser returned to Boston, on loan from the Navy, as a marine fire fighter berthed at the north end of the wharf at the foot of Copp’s Hill. While we know the fate of this particular 110, little is known of Harry Lappeman’s life after the war.

The image is courtesy of the Boston Public Library.

December 13, 2017 – Oscar Greenspoon

Oscar Greenspoon was born in Russia in 1890 or 1891. By 1917, young Oscar, whose parents were still in Russia, had opened his own tailor shop at 1508A South Grand in the city. Little did he know that his skills as a tailor would soon be put to work for the US military.

When drafted, Greenspoon found himself at Camp Funston, Kansas, with the 164th Depot Brigade where he completed his basic training. A month later, he became part of the aviation section, mobilizing at Camp Sevier, South Carolina, before joining the 1107 Aero Squadron overseas. Oscar was not, however, one of the famed “aces” of the AEF. Rather, he served an equally important job as a member of a maintenance crew that allowed the “Cavalry of the Clouds” to do their jobs.

Sailmakers were crucial to the American Expeditionary Forces air war. Even Mrs. Woodrow Wilson in a newspaper column in the spring of 1918 mentioned the need for these skilled individuals, who, along with mechanics, riggers, cabinet makers and others, helped keep planes in the air. If a plane required maintenance to the skin on the wings, referred to as “sails,” it was the sailmakers who helped patch or replace it regardless of whether it was covering a bullet hole or repairing a more severely damaged plane.

These aircraft were basically wooden frames over which was placed strong Irish linen covered with a dangerous but necessary mixture that the squadrons called “dope.” This coating, a mixture of ether, banana oil, gun cotton and sulfuric acid caused the fabric to contract and tighten, making it impervious to moisture and creating a smooth surface that reduced friction. Each repair or replacement wing received four coats of “dope.” While it might not sound as glamorous as a pilot, jobs like that of Oscar Greenspoon were crucial.

“Sailmakers” were highly recruited by the military. These tailors or civilian seamen were critical to the air war, repaired army tents, operated and maintained canals and waterways in Europe, as well as manned ships on the sea. In fact, they were so necessary that the government initiated a special sailmakers draft in early November 1918, only days before the Armistice.

Like others, Oscar Greenspoon returned to his home in St. Louis after discharge and resumed his life as a tailor and merchant along South Grand. Although he moved a few miles south of his pre-war business location, Oscar continued his business at 3220 S. Grand throughout the 1950s.

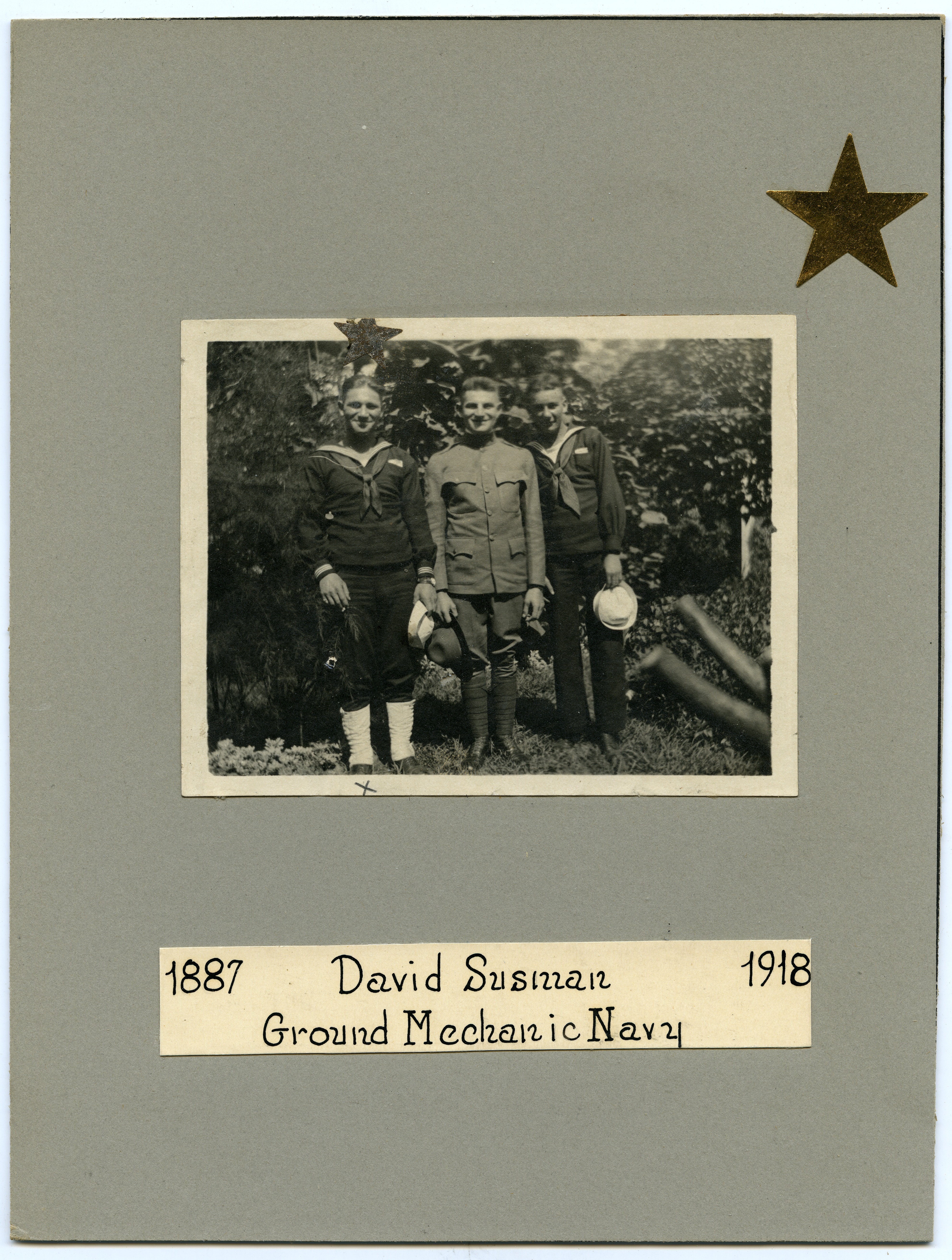

December 6, 2017 – Dave Susman

By the time young St. Louisan Dave Susman died of influenza September 28, 1918 in the Great Lakes Naval Hospital, the flu pandemic was already into its second deadly wave. Of medium height and build, Susman had graduated from Soldan High School and then worked at Weil Clothing Co. at 8th & Washington Avenue before being drafted. He arrived in the Great Lakes Naval Training Center in late July 1918 and two months later was in thehospital there. Two days after entering the hospital, Dave Susman died only nine weeks after joining the military.

Although Susman served only a short time, he still died in the service of his country and was remembered as such. His name is included on the WWI memorial tablets at Soldan High School and Temple Israel. It appears also on the Cenotaph at the Soldiers Memorial in downtown St. Louis. And in the early 1920s, the Gold Star Mothers honored him and 1,184 others with a bronze plaque and sycamore tree along Kingshighway (Susman’s was at Shirley Place & Rosalie Avenue on the north side of Kingshighway). Today, those plaques salvaged from that memorial are part of the WWI Court of Honor at Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery.

The flu pandemic acquired the name “Spanish Flu” because that country, unlike the US and the fighting European nations, did not censor its news and therefore was among the first to report influenza deaths. It has been suggested, however, that it is more likely the influenza originated in France or even among Asian war workers. The first confirmed case in the US was at Camp Funston, Fort Riley, Kansas. Unfortunately, spread of the influenza through coughing and sneezing was accelerated by the close quarters of the troops and their movements around the globe.

The first wave of the pandemic began in spring 1918, the second, more deadly, one arrived in September of that year. It has been recorded that the flu killed 200,000 in the United States in October 1918 alone. The third wave came in the winter of 1919. Dave Susman was one of an estimated 43,000 US servicemen who died from influenza.

The civilian population was equally susceptible to the flu. St. Louis Health Commissioner Max Starkloff tried many different restrictions to try to lessen its spread. He ordered mandatory reporting of influenza and pneumonia cases. He asked the police to refrain from jailing non-violent criminals, and, of course, he quarantined Jefferson Barracks. He enacted a ban on all non-essential businesses, and large gatherings such as schools, religious services, and other public crowds were also prohibited.

The US Surgeon General reported 3,396 new cases on influenza among soldiers in the home army for the week ending November 22, 1918; there had been 4,485 cases the week before. The “Spanish Flu”, also known as “La Grippe,” infected approximately 1/5 of the world’s population and killed between an estimated 50-100 million individuals around the world during 1918-1919.

The image is courtesy of the Missouri History Museum.

November 29, 2017 – Meyer Slein

Meyer Slein, born in Odessa, Russia, sometime between 1895 and 1898, immigrated to St. Louis with his family in 1904. They chose St. Louis because Meyer’s maternal uncle, Joseph Nudelman, had come to the city earlier and established himself as a tailor. Unfortunately for the family, Meyer’s father could not adjust to life in America and returned to Russia, leaving the family to fend for itself. Meyer and his younger brothers also had a hard time in St. Louis. They were constantly in trouble, often finding them in the Industrial Reform School. Although their mother remarried (some of the boys often used their stepfather’s last name of Bogdanow/Boddanov), things didn’t get any better for the family, and by 1910, sociologist Lewis Hine photographed the Slein brothers, young street kids who kept bad company, as part of his work with the National Child Labor Committee.

sociologist Lewis Hine photographed the Slein brothers, young street kids who kept bad company, as part of his work with the National Child Labor Committee.

It is unknown what happened in Meyer Slein’s life between those famous photographs and his military induction at Jefferson Barracks on April 1, 1915, except that he declared his intention to naturalize in 1914. Meyer’s life as a soldier during WWI was one of travel to parts of the world most people didn’t even think about in terms of the war. First he went to the Philippines as part of the 8th Infantry, where they were tasked with keeping the peace in that US territory.

But in 1918, Slein found himself transferred from the tropical Philippines to frigid Siberia with the 31st Infantry. American troops, along with British, French, Italian and Japanese soldiers, were to assist with the withdrawal of the Czech troops there, open the Trans-Siberian Railroad, and guard Allied supplies that had been sent for use by the then-dissolved Russian army. Meyer’s company was tasked specifically with guarding the valuable Suchan coal mines 75 miles west of Vladivostok, coal used to fuel the Trans-Siberian Railroad.

Meyer Slein’s military career did not end with the Armistice. He is listed in the 1920 census as still in the Army, married, and back in the Philippines. Although it is somewhat difficult to trace his military career fully after that time, it is known that he was in the Army (19th Infantry) bound for Hawaii Territory in 1922, then to the Panama Cana Zone in 1927 before returning to New York where he was discharged in 1929. The 1930 census shows him living with members of his Bogdanow and Slein family in Newark, New Jersey, and working as a barber. Obviously the pull of the military, or perhaps it was the security of the service, caused him to register for the draft in 1942, although he did not serve. Meyer Slein died of unknown causes the following year and was buried in the Fort Leavenworth National Cemetery.

Lewis Hine photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

November 21, 2017 – Allen Pastelnick

Allen (or Eli A.) Pastelnick was born in Russia in 1895. He entered the University of Missouri-Columbia in 1914, but soon made his way to Ohio State University where he was enrolled in the College of Arts-Education. But like others, he registered for the draft here in St. Louis because it was his home town. Pastelnick noted on his draft registration card that he had served three years in the Missouri National Guard, but was currently a student. By May 19, 1918, he was already in France with the 140th Ambulance Corps of the 110th Sanitary Train.

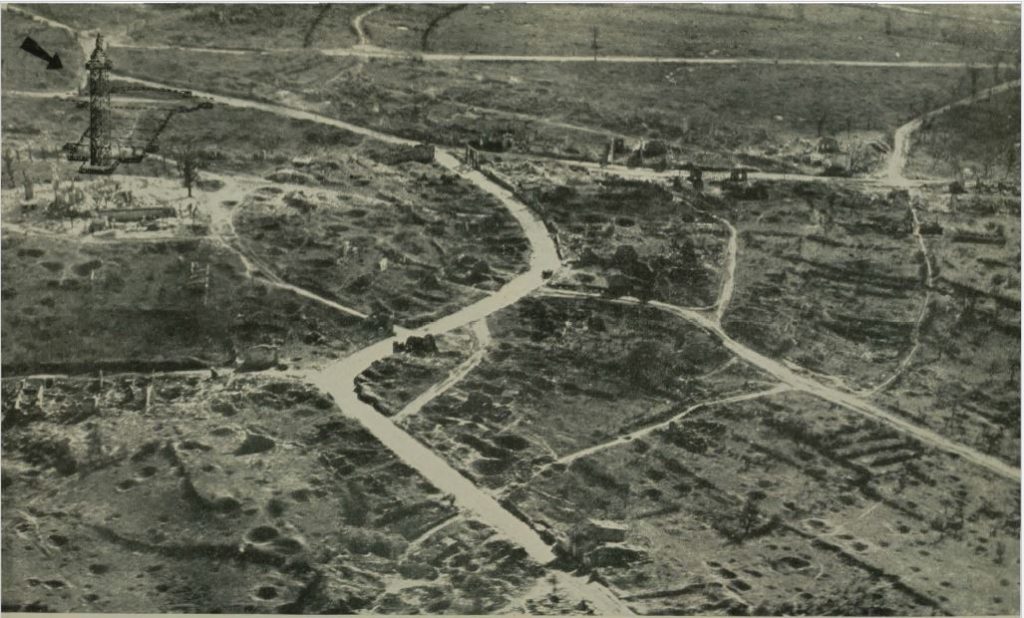

Among the striking items associated with Pvt. Pastelnick is a letter he wrote to Ohio State history professor A.M. Schlesinger in October 1918 [Ohio History Connection, WWI Collection, MSS 247, Box 1 f.20]. Prof. Schlesinger had taken it upon himself, along with another professor, to gather information about those from Ohio who had served in the war. In the letter, Pastelnick tells of his “bad dream” of being in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive of the war, beginning on September 26 when “our ‘doughboys’ (among whom were many of my former associates and friends) went over the top.” Pvt. Pastelnick was among those who manned a dressing station created out of two small cellar rooms of what had been a private home, tending to the wounds of those doughboys. He tells of how he and his fellow medics dressed the battle wounded, stopping during the first 24 hours only to have a cup of cocoa and resting on the dirt floor when it became too dark for stretcher bearers to find the wounded and for him and others to tend the injured.

Pastelnick goes on to tell of the harrowing trip in the early hours of September 30 when they were told to evacuate the station, which he and others called “our strategic retreat.” Shrapnel and shells burst around them as they were literally running for their lives through bombed-out areas, over hills, across wire, and through mustard gas attacks. Toward the end of his letter he wrote that those who wake up from the “bad dream” will have “a greater confidence in all people regardless of race, color or religion” – except for the Hun.

Pastelnick survived the war and married Pearl Deutch in St. Louis in 1921, a ceremony performed by Rabbi Abraham Halpern at B’nai Amoona. Sometime between 1921 and 1930, he changed his last name to Pastel, and his 1970 New York Times obituary recalls his St. Louis real estate career before he moved east in 1950. He had lived in Manhattan before moving to East Norwich, Long Island, participating for 20 years in local politics before his death.

The photo is courtesy of the American Battle Monuments Commission.

November 15, 2017 – Horckitz Brothers

Brothers Joseph J. and Nathan Horckitz were born in St. Louis, and they both served as privates in the Air Service at Scott Field during WWI. Joe, the older of the two at age 22 had been a salesman for Walkover Shoe Co. before being drafted and arrived at Scott Field in late summer 1918; Nat was 20 and got to the Field two days after his brother. They were the sons of Morris and Sophia Horckitz, Austrian immigrants who came to the US in 1888 and naturalized in 1893.

Scott Field, named in honor of Cpl. Frank Scott of the Army Aviation School at College Park, MD who had died in a flying accident at the school in 1912, was one of the youngest primary schools in the Army’s Air Service. When the Horckitz brothers arrived in August 1918 the Scott Field, which was under lease to the Government, was almost complete with 18 steel hangers built to house six planes each and paving of the road between it and Belleville underway. Flight cadets had been there for almost a year, along with several hundred enlisted men who served as mechanics, repairmen, woodworkers and just about everything else the Field needed.

Aviators training at Scott Field received basic flight instruction in one of the $8,000 Curtiss “Jenny” or standard dual-control planes. After six hours of flying with an instructor cadets could make their solo flight. Pilot trainees received three hours flying time daily, along with radio and/or wireless telegraphy training, instruction in the use of rifles and machine guns, as well as regular drilling. Advanced flight instruction took place at other camps in the US or in France. Of course, none of that could be done without the constant upkeep of the planes.

Although the Horckitz brothers were not pilots, it was their work at the base that helped keep the planes in the air. After service at Scott Field, both Joe and Nat were transferred to the Aviation General Supply Depot in Little Rock in December 1918, where they served until their discharge early in 1919.

The image is courtesy of the Library of Congress.

November 8, 2017 – Albert Alois Aufrichtig

Albert Alois Aufrichtig was born in St Louis in 1895. His father, Alois Aufrichtig, was already a skilled tradesman when he left Hungary, so it is not surprising that he founded a successful copper and sheet metal company in St. Louis that marketed to the rapidly growing brewing industry. In 1881, Alois married Jennie Lederer, who came to St. Louis with her two sisters from Bohemia as a teenager. In 1910, young Albert was featured in a St. Louis Post- Dispatch article about the enthusiastic and mechanically-talented band of “boy aviators” who were invited to the first annual National Aero Show produced by the Aero Club of St. Louis. Albert Bond Lambert, Aero Club President, promised a discounted entrance fee to the boy aviators with the balance refunded if their model flew a hundred feet.

By 1914, Jennie Aufrichtig, now a widow, decided to travel to Europe, taking her youngest son Albert (nicknamed Ollie) with her. Jennie and Ollie were having a wonderful trip when they were surprised by the sudden outbreak of hostilities. They dashed to the coast where they were fortunate to gain passage on the steam liner SS Philadelphia, the last ship to leave England for the US. Many other Americans were also caught off guard, many of whom could gain passage only in steerage. It was reported that President Woodrow Wilson sent a wireless message to the ship asking that they allow steerage passengers to mingle with the other passengers. The ship arrived in New York City on August 13, 1914, where Jennie, along with a number of other passengers, was interviewed for a feature story in the New York Times.

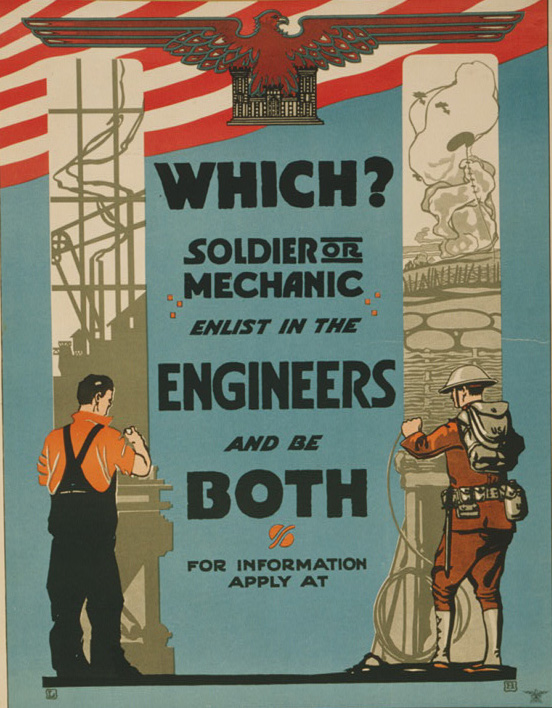

Albert was employed by his father’s company, the Alois Aufrichtig Copper and Sheet Iron Company at Third and Lombard Streets, when he registered for the Selective Service draft on June 5, 1917. Although he requested exemption from service for occupational and physical reasons, by April of the next year he volunteered in response to an urgent appeal for Army vocational trainees along with 249 other men from St. Louis. Assigned to Soldan and Central High Schools, they learned one of four mechanical trades: woodworker, machinist, blacksmith, and gas engine mechanic. All the trainees lived together at Lodge Barracks (5512 Etzel Avenue), which was supervised by the YMCA. They awoke at 5:45 am each day and wore blue overalls because their uniforms had not yet arrived, attended lectures and workshops for seven hours each day along with two hours of military instruction. And they could visit home on the weekends, except for when they were confined to quarters during the influenza epidemic. In October 1918, Albert was promoted to Corporal and reported for service at Camp Hancock in Georgia. He was discharged from the Army on January 4, 1919.

November 1, 2017 – Alexander S. Dawson

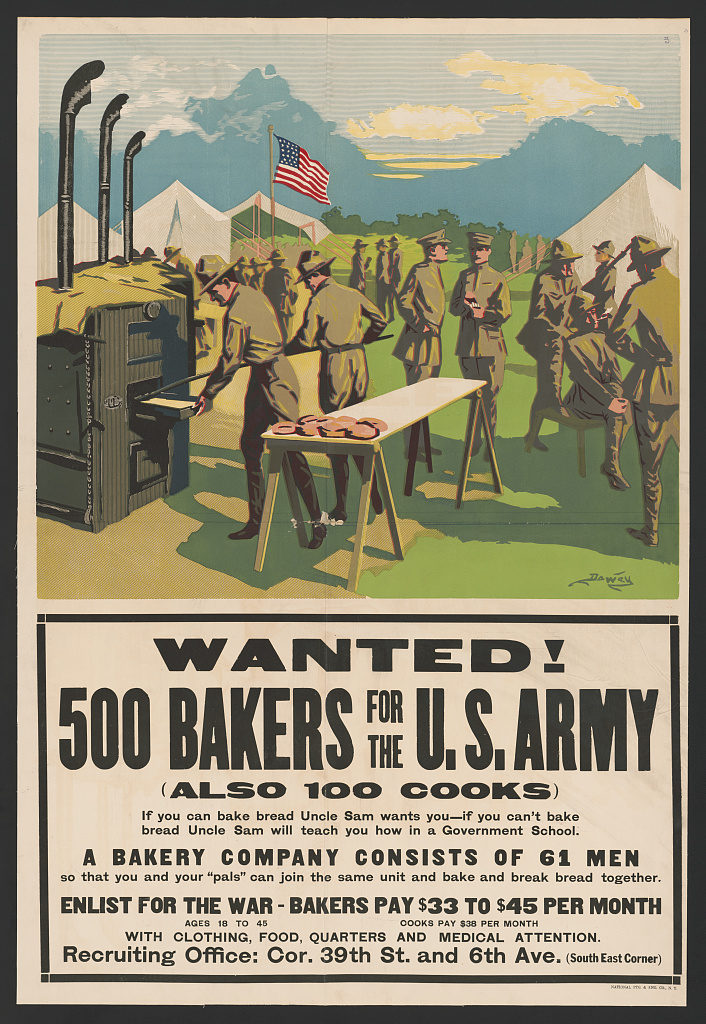

They say an army fights on its stomach. That’s certainly what tall, slender Alexander S. Dawson found out when he enlisted and was assigned to Bakery Company No. 8. Apparently his organizational skills as the assistant paymaster of the St. Louis-San Francisco Railway Co. served him well in the military. Although this St. Louis soldier was stationed in the US, he certainly knew the demands of making bread and biscuits for his fellow combatants.

Officially part of the Quartermaster Corps, Lt. Dawson was responsible for making sure the men under his command – bakers and cooks – kept the men on the base fed. The military made a push to recruit more bakers in July 1917, offering them $37.75 per month while stationed in home territory and $45 per month if stationed overseas. By May 1918, the US had 88 bakery companies with 8,880 enlisted men. They had even established baking schools to train the men they needed.

Soldier rations included about one pound of bread per day, which meant that a garrison usually made around 34,000 pounds of bread daily. Thus during the war, home cooks in the US (and in Europe) were asked to lessen the amount of bread consumed as well as to substitute other grains for bread so that the army could use most of the white (wheat) flour. US Army field bakers, who experimented with doughs and yeasts, had a much harder time providing fresh bread for the troops, but they did their best. Not only did they have more difficulty getting needed ingredients, but they also had to bake in movable ovens placed in tents. Soldiers in the trenches often had to settle for emergency tinned rations, which included bread and meat cakes that could be eaten dry or boiled, making a porridge or “palatable” soup depending on the amount of water used.

October 25, 2017 – Walter J. Bauman

When Ste. Genevieve-born Walter J. Bauman registered for the draft on June 5, 1917, he recorded that he lived on Delmar and was a mechanic for a business at 4900 Page Avenue. Three months later, he found himself among the first St. Louis draftees on their way to train at Camp Funston. Perhaps it was his work as a mechanic that led Bauman to become a wagoner with the 314th Engineers Train, part of the Kansas, Nebraska, Colorado and Missouri men who made up the 89th Division.

As a wagoner, Bauman was responsible for an army vehicle, the animals that pulled it, as well as the cargo it carried. Those vehicles could be ambulances, escort wagons or carriers of goods. Wagoners were accountable for the grooming, watering, feeding and care of the animals, whether horses or mules, as well as the maintenance and repair of the wagon. While wagons were already being replaced by motorized vehicles, their use was still essential to the war effort.

Wagoner Bauman and his fellow soldiers of the 314th Engineers, found themselves on the RMS Carpathia in June 1918, six years after that ship helped rescue the survivors from the Titanic and one year before it was sunk off the Irish coast by a German submarine. After landing in England, the 314th made their way to Cherbourg France and their first military engagement in the Lucey Sector (Lorraine). They would go on to fight in the St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne Offensives before the Armistice. They then became part of the Army of Occupation, serving in Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany.

Walter Bauman made it back safely to New York on May 23, 1919 aboard the USS Harrisburg with his fellow Engineers, 110 horses and 40 motor vehicles.

October 18, 2017 – Balloon Corps

The Army Balloon Squadron, organized under the aviation section of the US Signal Corps during the war, was one of the smallest groups in the American Expeditionary Force (AEF). Commonly referred to as the Balloon Corps, 102 American balloon companies existed during the Great War, although most were either stationed stateside, like Hollibert O. Evans with the 22nd Balloon Aviation stationed in Waco, Texas, or were in transit at the time of the Armistice. Thirty-five companies served in France, but not all saw combat. St. Louisan Max Weinstock of the 17th Balloon Co. was one of those who made it overseas (October 2, 1918-May 3, 1919). Of the 20,000 officers and enlisted men in the Balloon Corps, only 685 were rated as pilots or observers.

Fort Omaha was the primary center for balloon training during the early part of the war, having a large steel balloon hanger and hydrogen plant already in place from earlier in the century. Later in the war balloon training moved to Camp John Wise in San Antonio, Texas, when it was realized that Omaha was not conducive for balloons.

Most AEF balloon companies on the front used American-made French Caquot kite balloons. These interesting balloons were attached by tethers to a truck winch so they could be moved up and down and place to place, quickly if needed, and had a gondola beneath that could accommodate two passengers. Able to rise to 4000 feet in good weather, most stayed closer to 1000 feet and helped to direct artillery fire as well as reporting on enemy airplanes, military traffic on roads and railroads as well as the location of enemy artillery batteries.

Unfortunately, these hydrogen balloons were highly flammable and easy targets of the enemy. Even so, by the end of the war the squadron reported that only 12 balloons had been destroyed and 35 burned. And observers only had to jump from their gondolas 116 times!

Not everyone who died in the service of the Balloon Corps was killed on the front. St. Louisan Alfred Kreisman died of pneumonia while at the Omaha Balloon School. Part of the medical division assigned to the school, he had formerly worked at Barnes Hospital before being assigned to the school only six months before his death in October of 1918.

October 11, 2017 – Albert S. Aloe

Sgt. Albert Sidney Aloe came from a long line of well-known St. Louisans. His name-sake ancestor founded the A.S. Aloe company here in the 19th century, a prominent manufacturer and distributor of surveying, optical and surgical equipment. In fact, it was young Albert Aloe’s experience working in the family business that led to his appointment on the army medical staff and then to a Mobile Optical Unit in France.

Sgt. Albert Sidney Aloe came from a long line of well-known St. Louisans. His name-sake ancestor founded the A.S. Aloe company here in the 19th century, a prominent manufacturer and distributor of surveying, optical and surgical equipment. In fact, it was young Albert Aloe’s experience working in the family business that led to his appointment on the army medical staff and then to a Mobile Optical Unit in France.

After a brief training period at Walter Reed Hospital, Aloe and other opticians found themselves at Camp Crane in Allentown, PA preparing for deployment to France. In 1917, the military standardized the types of lenses and white frames for personnel. Soldiers could obtain the required eyeglasses at base post exchanges after visiting the optician assigned to each base hospital. But they realized that there was still a need for optical units overseas. Thus, the Army created a base optical unit and (originally) eight Mobile Optical Units overseas for use by US and Allied forces.

Each unit was a self-contained eyeglass facility, stocked with frames and lenses as well as the equipment and machines needed to fit and fill prescriptions. For a year in France, April 1918-April 1919, Albert Aloe was one of the opticians who manned one of the Mobile Units. The Army optical program furnished 2.5 million eyeglasses in the war effort. After his service in France, Albert Aloe served in embarkation camps on the East Coast, providing eyeglasses and, when necessary, artificial eyes to returning soldiers.

October 4, 2017 – The Fighting Rosecans

Brothers Edward and Adolph Rosecan referred to themselves as the “fighting” Rosecans. Young Adolph was not yet 16 when he enlisted in the Navy in June 1917. Older brother Edward followed him a year later, both of them first to the Great Lakes Training Center and then the Receiving Ship Philadelphia. While Adolph stayed on the Philadelphia longer, followed by service on the USS Carola, brother Edward’s time on the Philadelphia only lasted a month before he took up service at the Naval Barracks on Gibraltar. His last duty assignment was on the torpedo-boat destroyer USS Dale before being discharged.

At one time, Seaman 2nd Class Adolph Rosecan wrote of his excitement of becoming a member of the bugle corps. In February 1919, Adolph was discharged from the Navy at the Naval Hospital at Mar Island, California. Seaman Edward Rosecan, an amateur boxer, once wrote that he won a Sailor-Soldier-Marine boxing tournament when he knocked out a Marine in two minutes. In the same letter Edward noted that he was off either to Siberia or to France, it didn’t matter which one. Thus the “fighting Rosecans” was not a title to be taken lightly. Edward even gave the brothers a motto: “Berlin or Bust.” Neither made it to Berlin, but they did serve honorably in the Navy.

Edward Rosecan had one additional adventure, witnessed while stationed on Gibraltar. There on November 9, 1918, two days before the Armistice, he watched the German submarine UB 50 torpedo and sink the British battleship HMS Britannia. The Britannia had been doing troop convoys along the West African coast when it was hit and sunk while coming through the Straits of Gibraltar.

Interestingly, in the interwar period, the two brothers once again mirrored their profession, but this time it was in the motion picture business. By 1940, Edward had become the owner of a movie theater in Hannibal, while Adolph was the manager of the popular Princess Theater, an outdoor movie house on Pestalozzi St. in St. Louis.

September 27, 2017 – Fourragère

The now official motto of the Marine Corps is: Once a Marine, always a Marine. Once an individual has earned the title Marine, he/she remains a Marine for life. That is certainly true of St. Louisans Theodore Lending and Hyman A. Nudelman. Although neither was born in the US, they both became Marines, fought in some of the fiercest battles of the war, and like others in the 5th & 6th Marines received the right to wear the French Fourragère proudly on the left shoulder of their uniforms.

Theodore Lending, born in Warsaw just before the turn of the 20th century, enlisted in the Marines in January 1917 and found himself on the battlefields of France in June of that year. He would serve more than two years overseas with the 5th Marines, severely wounded in the Battle of Belleau Wood in June 1918, and erroneously reported killed in action for many months. Hyman A. Nudelman, born in St. Petersburg also just before the turn of the 20th century, served a little more than eight months overseas with the Marines, fighting in some of the same battles as did Lending.

The men of the 5th and 6th Marines had the single honor of being the only two regiments in the American Expeditionary Force to receive the Fourragère and the Croix de Guerre with two Palms and one Gilt Star. The French government awarded decorations for meritorious conduct in action to 156 American units during the war. Military units decorated twice with the Croix de Guerre with Palms were entitled to wear the braided and knotted cord known as the Fourragere in the colors of the Croix de Guerre (green & red). Thanks to the courage and actions of those men of the 5th & 6th Marines, even current members of those units are entitled to wear the Fourragère.

The photograph on the left is courtesy of the US Marine Corps, 6th Marine Regiment.

September 20, 20017 – Harvard Naval Radio School

In December 1917, several members of the St. Louis Jewish community – like Walter H. Bowman, Samuel Quicksilver, Leo H. Rosenheim, and Wilton Rubinstein – found themselves off to Harvard. It was not, however, for their university education, but rather to attend the Naval Radio School there.

The Brooklyn Navy Yard had been the site of the school before the war, but by the time the US entered the fighting it was out of space. So by July 26, 1917, Harvard found itself with more than 800 naval recruits there to learn about radio communications. It was not long before many of the campus buildings became either barracks or classrooms for the Navy. These young men spent seven hours a day in class and another two hours daily in military drill five days a week. Subjects included magnetism, batteries, electricity, alternating current, circuits, etc.

By the beginning of 1918, Harvard had about 3,000 radio students on campus, including St. Louisan Lawrence S. Glaser. In fact, there were so many sailors there that they had to attend instruction in two shifts, with classes running 7:20 am to 9:00 pm. At the end of 1918, the Harvard Naval Radio School graduated about 165 men each week. It is estimated that during the war about 8,400 new radiomen graduated from Harvard before being sent directly to the fleet.

The Harvard Naval Radio School and the thousands of young men who attended it clearly show how radio and radio operators had become essential to the war effort.

The image is Courtesy of the Cambridge Historical Commission’s Ephemera (CMS) Collection.

September 13, 2017 – Students’ Army Training Corps

On August 31, 1917, Congress authorized the creation of the Students’ Army Training Corps (SATC) as part of the Selective Service Act, even though the program didn’t officially begin until October of 1918. In July 1918, 60 day training camps were established at 525 educational institutions, and 200,000 students joined on the first day. Enrollment in the SATC was completely voluntary, unlike the Selective Service Draft, and gave students the rank of private in the US army. There was also a naval section of the SATC. Although the formation of the Corps was a part of the Selective Service Act, it was not a way of avoiding the draft. The Committee on Education and Special Training within the War Department administered all programs, giving each university/program a quota and approving all courses taught. Colleges and universities with at least 100 male students were considered for inclusion in the program.

Because all SATC programs were hosted on college campuses, they could utilize their pre-existing assets such as buildings, equipment and educators to train the officers and technical experts needed by the military. While all members of program drilled together, there were actually two sections of Corps: one vocational and the other collegiate. The vocational section focused on issues such as blacksmithing, metalworking, woodworking and airplane/auto repair. These students were not part of the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC), whose graduates were eligible for a military commission. Rather SATC students were inducted as Army privates upon graduation. Those who enrolled in the SATC received free room and board, clothing, and $30 per month. Some were later sent to Officer Training Camps to earn commissions. All SATC soldiers were dismissed in December 1918.

Many St. Louisans participated in the SATC program at Washington University. The result was a totally changed campus atmosphere. All university buildings, except the women’s dormitory, were involved in government work, and for at least one year the football team was undefeated!

Members of the St. Louis Jewish community known to have joined the SATC included:

Washington University, St. Louis: Julius Leon Block, Wilton Jerome Colonna (vocational), Alexander Fadem, Albert Feldman, Jess Klement Goldberg, Alfred Goldman, Frederick Goldwasser, Monroe Barney Gross, Albert Levin, Clarence E. Mange, Earl Rosen, Abraham Leo Sacher, Morris Tenenbaum, Walter J. Skrainka, Barney L. Schwartz, Donald Wachenstein

University of Missouri: Ralph Lowenstein, Emil Nathan Jr., Edwin Shroder

NW University, Evanston IL: William Friedman

Agricultural College, MS: George Steinwolf/Steinwolff (ROTC to SATC)

September 6, 2017 – US Guards

In December 1917, the US created a new military unit called the United States Guards under the control of the Chief of the Militia Bureau. Their task was to protect strategic installations and areas within the US, something that the federal military and the National Guard had done before members of both were called into combat. When organizing the Guards began in earnest, many of those who became part of the unit had been draftees “thoroughly trained (but) rejected for service overseas due to some minor physical defect.” Others members of the Guards were those over draft age. Somewhat like the Home Guards of earlier eras, these men protected bridges, shipyards, mines and essential utilities and businesses.

The US Guards were an auxiliary force of men between the ages of 31-45 (later they could request a waiver if older than 40). They could be married, veterans of earlier wars and military actions (such as the Spanish-American War, Philippine Insurrection), those who had served in the National Guard, or who were experienced police and fire personnel. Training was the key. They received the same pay as regular infantrymen and at first wore regular infantry dress uniforms. The public, however, disliked those uniforms for the Guards so the Quartermaster was ordered to furnish standard service uniforms. They were equipped with surplus (meaning unfit for use overseas use) rifles, ammunition and accoutrements. Although the military made every attempt to assign them near their home towns, that was often not the case. By the end of the war, 135,000 men had served in the US Guards

At least four members of the St. Louis Jewish community are known to have served in the Guards. Fred Henry Klein was born in Vienna, Austria, and had served in the Austrian military by the time he filled out his draft papers in 1917. He was a salesman for Stix, Baer & Fuller and had declared his intention to naturalize. He was drafted and served in various units between October 1917 and July 1918 before being moved to the US Guards in Fort Bliss, Texas.

Bernard Levy, born in East St. Louis, was already 30 years old when drafted. He was a stock clerk for the Red Diamond Co. in St. Louis when he began his military service. Serving briefly in the 349th Infantry, he was later assigned to the 163rd Depot Brigade, Camp Dodge, Iowa and then the 37th Battalion of the US Guards.

East St. Louisan Felix Loebner had been a mechanic’s apprentice with the Fletcher Typewriter Company in St. Louis before serving briefly in an infantry regiment, the 163rd Depot Brigade, and then with the 37th Battalion of the US Guards.

Finally, Russian-born Albert Zasslow was already 33 when he was drafted. He too served in the infantry before being transferred to the 163rd Depot Brigade and then serving in the 29th Battalion of the Guards.

August 23, 2017 – Jewish Legion

More than 2,700 Americans volunteered to serve in the British Army’s Jewish Legion during the Great War. These men, along with other recruited from Canada, Palestine and elsewhere, were trained to fight against the Ottoman Empire. The Jewish Legion, their unofficial name, was actually five battalions of Jewish volunteers who comprised the 38th-42nd Battalions of the Royal Fusiliers, with most Americans serving in the 39th. It is estimated that more than one-third of those deployed to the Palestine Front were Americans.

The first group of 18 St. Louis recruits departed in the late evening of April 31, 1918, but only after being banqueted by the Red Mogen David at the Jewish Educational Alliance, 9th and Carr Streets. There each recruit received a “comfort kit” that included various toiletries as well as a sweater, and the group was presented a silk Zionist flag. The next day, the enlistees were escorted, including a brass band, from the Jewish Legion recruiting station at 1507 Franklin Avenue to Union Station, a farewell celebration reminiscent of that for the first American draftees who left St. Louis the year before. The Legion’s recruits were first bound for Canada where they received their initial training, and then on to England, Egypt, and some on to Palestine.

The St. Louis volunteers trained first at Fort Edward in Windsor, Nova Scotia, alongside Canadian and British volunteers like the young David Grun, later known as David Ben-Gurion, and Vladimir (Ze’ev) Jabotinsky. Three recruits from St. Louis – Abraham Levin, Aaron J. Bashkow and Morris B. Seligsohn – were promoted and trained as non-commissioned officers. Sgt. Levin, having returned to the city on leave in June 1918 to assist with Jewish Legion recruitment, extolled the conditions at the training camp in Nova Scotia, including its delicious kosher food and the great climate.

The 39th Royal Fusiliers arrived in Palestine in the summer of 1918 where they joined British soldiers already fighting north of Jaffa. In September, they participated in the Battle of Megiddo, and it was during that month they were tasked with fording the Jordan River, along with the 38th, in one of the final battles on the Ottoman Front. After that, some Jewish Legionnaires served as guards of enemy combatants until the fighting in Palestine was finally over.

The following individuals from St Louis are reported to have enlisted in the Jewish Legion:

B. Arnoltz, Aaron L. Aronow, Ben Axelbaum,Jake Axelbaum, Hyman Baltzman, Hyman Bamholtz, Aaron J. Bashkow, Morris Aaron Bashkow, Benjamin Berger, Abraham Broun, Ben Cohen, Jacob S Cohen (the first recruit from STL), Julius Corman, Jack Cron, Morris Edelman, Harry Edlin, Edward Eisen, Leon Epstein, Manuel Essman, Henry Feigenbaum, M. Fierson, Louis Friedman, C. H. Galpern, Elias Ginsberg, Jake Gishes, Morris Glassman, Morris Goldberg, Julius Gruenkel, H. Halperin, Isaac Hoffman, Nathan Hurwitz, Meyer Ikin, Morris Jick, Samuel Kashenover, Julius Kerman, S. Kersman/Kerman, B. Klaimon, Jacob Koplar, Woolf Korabelnik, Sidney Kron, Abraham Levin, Abraham Moinester, Isaac Moinester, Morris Pearson, Arthur Rabinovitz, Israel Rosen, Ben Roth, Nehemia Rubin, Abe Schneider, Sam Schuchman, Morris B. Seligsohn, Morris Sheiman, Sam Smolensky, Benjamin J. Solkoff, Louis Sosna, Charles Spelky, Isaac Turvoitz, Aaron Washkoff, Dave Weiss, Edward Wining, Harry Wolfson, Hyman M. Zuckerman, David Zukerman, and Abraham S. Zubov.

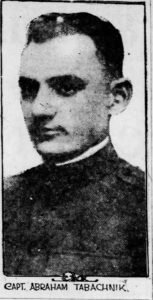

August 16, 2017 – Abraham Tabachnik

Abraham Tabachnik was born in Cincinnati but moved with his family to St. Louis when he was about nine years old. After graduating from Central High School, he spent one year at Washington University before transferring to the University of Missouri, where he earned a B.S. in Civil Engineering in 1916. It was then he enlisted in the military and was commissioned as a 2nd Lt. After being promoted to 1st Lt. in November 1916, he made captain after he arrived in Europe in June of 1917.

As an observer in the 91st Aero Squadron, “Cap’n Abe” found himself in the thick of things in an air battle on the second day of the St. Mihiel attack, September 14, 1918. After having gone up earlier in the day with a new pilot and three other planes, they dodged anti-aircraft shells and made it back to base. But the day was not over.

As an observer in the 91st Aero Squadron, “Cap’n Abe” found himself in the thick of things in an air battle on the second day of the St. Mihiel attack, September 14, 1918. After having gone up earlier in the day with a new pilot and three other planes, they dodged anti-aircraft shells and made it back to base. But the day was not over.

In a letter to his parents, Tabachnik related what happened when the formation took to the sky again that afternoon. They had taken the photographs they needed and were on their way back to base when six, then 12, and finally 20 German planes attacked. Tabachnik himself explained what happened next. “I got an explosive bullet in my right arm, and down into the cock pit I went. I lay there semi-conscious for a few seconds when I realized that I still had use of my arm, so up I came and the fight was on again. Another Hun dived at us and a bullet went through the fleshy part of my arm just below the elbow. Then three came in together and shot the machine gun out of my hand, a bullet just clipping the knuckle of my right index finger. Then I was ‘out of luck’ for fair, machine gun useless, right arm stiff, and all I could do was to wait for them to get either me or the pilot.” However, Capt. Tabachnik and his pilot, as well as two of the other US planes, made it back to base.

Abraham Tabachnik received two citations for extraordinary bravery for his actions that day in the vicinity of Lachaussee. Not only did he continue to fighting in spite of his wounds, he held his machine gun in position and returned fire, taking down one enemy plane. Tabachnik made the military his career, gaining the rank of Colonel before retiring in 1945. He had served in WWI and WWII, and was head of the University of Illinois’ ROTC (Pershing Rifles) and professor of Military Science and Tactics in the 1930s. Col. Tabachnik died at Fort Benning, Georgia in 1962. He is buried in United Hebrew Cemetery in University City, Missouri.

August 9, 2017 – Frederic Albert Arnstein

Like so many others, St. Louis-born Frederic Arnstein found himself in the US military in 1917. Frederic’s father, Albert Arnstein, was a well-known lawyer and member of the St. Louis City Council 1891-1895, who also helped establish such Jewish institutions as the Hebrew Free Industrial School and the Home for Aged & Infirm Israelites. At an early age, Frederic played violin in the Victor Lichtenstein’s People’s String Orchestra and attended St. Louis University’s School of Commerce and Finance. But when the US entered the war, Arnstein joined the Navy. After boot camp at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station and then radio school in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the tall, gray-eyed Arnstein became a radioman on the USS Tanamo.

A British-built ship (1914) originally called the Van Nogendorp, the Navy chartered the now USS Tanamo in August 1918 and commissioned it as part of the Naval Overseas Transportation Service (NOTS) as a refrigeration supply ship. The Tanamo was one of 16 Navy ships with refrigerated holds used to carry frozen food stores and other needs to our troops in Europe. On its first trip to France, the Tanamo carried a cargo of beef and 57 trucks. Unfortunately, that shipment never made it to Europe due to boiler trouble. A few months later, and after repairs, the ship made it to Verdon, France, and unloaded its cargo. Two months later it carried 1479 tons of beef and a large number of trucks to St. Nazaire. In February 1919 the Tanamo made its last crossing as a naval vessel and was decommissioned in April of that year and returned to its owner, the Sarnia Steamship Corp.

Before the war, Frederic Arnstein worked as a broker for Stix and Co., an investment brokerage firm in St. Louis. After the war, he returned to his job as an investment banker and in time became a partner in the firm. He died in 1957 at the age of 65.

The image is from the Naval History & Heritage Command.

August 2, 2017 – Joseph D. Richter

Gray-eyed, Baltimore-born Joseph D. Richter came home from the Great War missing his right arm. Before he enlisted, he had already served three years in the Missouri National Guard with the rank of sergeant and was a clerk at Famous-Barr at 7th & Locust in downtown St. Louis. By June of 1917, he was already on active service in France. He had spent 12 days in the Alsace sector and 12 more in the Lorraine sector before being sent to Verdun. But it was the fighting in the Argonne forest that would change his life.

Joseph Richter’s story is one not only of heroism on the battlefield, but also of eloquence and determination at home. Although his parents Jacob and Julia Richter had previously been informed that their son had been gassed, in December of 1918 they learned that he had been severely wounded and was on his way home – first to a debarkation hospital in Hampton, Virginia and then to Fort Des Moines Reconstruction Hospital for treatment and rehabilitation.

At 5:00 am on the morning of September 28, 1918, Richter and his comrades of E Company 138th Infantry had been ordered over the top in the battle of the Argonne. Like the other soldiers, he ran – encountering guns and trip wires, getting caught in crossfire, and outrunning their artillery support. Even when Joseph became separated from his company, he kept advancing. He recalled encountering a German soldier coming toward him after going about two miles. Private Richter charged him with his bayonet, but when the German yelled “kamerad,” Joseph lowered his gun. That’s when the German rushed him again and Richter shot him. Joseph Richter continued his advance finally falling into a shell hole with shells bursting all around him. The next thing he knew, he was in a hospital.

While in the Fort Des Moines hospital, Richter said, “I’m not asking for any sympathy. All I ask of the people of St. Louis when I get back is a square deal.” And although he and others there said they regretted their wounds, they had done their duty and would do it again. Private Richter also commended the Salvation Army and Red Cross workers. “What we fellows did was necessary to save our lives and the lives of countless others. We had to do it. But these men and women up just a short distance behind the lines passing out doughnuts and comforting us didn’t have to do it and that is what makes their work all the more wonderful.”

When the rest of E Company made it back to St. Louis, Richter was there to greet his former comrades. He told one, “I can whip you now.” When one joked, “Why did you run away and leave me,” Richter replied, “You were running so fast chasing Huns I couldn’t keep up.”

The image is Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

July 26, 2017 – Milton Roy Stahl

Milton Roy Stahl was apparently born to serve.

Born in St. Louis in 1893, he graduated from Central High School in 1911 and then attended the University of Missouri and Washington University Law School. However, his law school career was interrupted while attending the University of Paris in 1917. There, within one year of graduation from law school, Milton Stahl entered the US army, 340th Field Artillery. The newly-commissioned 2nd Lieutenant found himself in France, on the front, with the 89th Division where he served through July 1919. The Division saw fighting in the St. Mihiel and Argonne offensives and had crossed the Meuse by the time of the armistice.

One might think that was enough service for one person’s life, but not for Milton Stahl. He returned to law school, receiving various honors along the way, graduated and joined the firm of Nagel & Kirby. He was also a lecturer on medical jurisprudence for the Washington University School of Law faculty. As if that wasn’t enough, Milton Stahl also served as the Chair of the Missouri Public Service Commission and as a Commissioner of Welfare in the late 1920s into the early 1930s.

One might think that was enough service for one person’s life, but not for Milton Stahl. He returned to law school, receiving various honors along the way, graduated and joined the firm of Nagel & Kirby. He was also a lecturer on medical jurisprudence for the Washington University School of Law faculty. As if that wasn’t enough, Milton Stahl also served as the Chair of the Missouri Public Service Commission and as a Commissioner of Welfare in the late 1920s into the early 1930s.

Having married and returned to St. Louis, he became head of the Trust Department of Mississippi Valley Trust until, once again, he felt the need to serve. In 1942, he left his job with the Trust and re-entered the military as a captain in the US Army Air Corps. In early 1944, now Major Stahl was attached to a heavy bombardment group in Europe and asked his friends in St. Louis to send their old Baedeker Guide books to him for his bombing crews to use because of their detailed maps and local information. Not long he was attached to the intelligence branch of the 8th Air Force in Britain and was part of the briefings for D-Day. After the war, Major Stahl moved to Dayton, Ohio where he lived until his death in 1961. For many, it was a relatively short life, but one of tremendous service to the State of Missouri and the nation.

The image is from the State of Missouri: Missouri Public Service Commission.

July 19, 2017 – Gilbert R. Loewenstein

Tall, blue-eyed Gilbert Loewenstein registered for the draft in June 1917, just like so many other young men. The single, 21-year-old former St. Louis University student (School of Commerce and Finance) soon found himself in another world.

When Loewenstein arrived in Europe October 27, 1918, he was assigned to a tank corps battalion, something relatively new in the world of warfare, although possibly something not too foreign to him after having worked with the Michigan Central Railway before the war. Tanks were not quite the same as they are today. Developed because of the impasse and increasingly large loss of life along the Western Front, tanks at the time were slow and manning them was dangerous. If the tank did not get a direct hit by artillery or mortar shells, the crew could be overcome by the hot and stuffy atmosphere inside with the added danger of gas fumes from the engines and shells. There were no US-produced tanks used by the AEF during the war, so American forces tended to use French Renault FTs or British tanks. Probably the biggest problems with tanks during the Great War were mechanical break downs and communications. Without radios, the AEF tried both carrier pigeons and junior officers walking beside the tanks to relay/accept orders.

Gilbert Loewenstein apparently did well and was later stationed with the 8th Army Tank Corps headquarters, then the 3rd Army Tank Corps headquarters in Europe. In August of 1919, he was posted back in the US at Camp Grant in Rockford, Illinois. Camp Grant was created as an induction center in 1917 and the home to 40-50,000 soldiers during the war. At the end of the war, Loewenstein helped form and was the historian for the Jackson Johnson Jr. (American Legion) Post of the Tank Corps, named as a tribute to a fellow tank man who died of the flu in England a month before the armistice.

Other Jewish St. Louisans in the tank corps did not do as well as Lt. Loewenstein. Thirty-six year old Harry Henry Cohen died less than a month after his service began of an abdominal hemorrhage. Young Jacob B. Rosenblatt survived the war by only three years after suffering 75% disability after serving in the tank corps.

The image is from the Missouri History Museum and is a showing of military weaponry in Forest Park after the war.

July 12, 2017 – Henry L. Rothman

Of all those who served in WWI from the St. Louis Jewish community, Henry L. Rothman is the only one known to have been held as a prisoner of war by the Germans. Born in Missouri in 1889, Henry L. Rothman became a doctor just like his father and brother, and opened a practice in Washington, MO in 1916. About a year later, he received his Army commission, and Lt. Henry L. Rothman entered service at Camp Doniphan in late summer of 1917. By late April 1918, he was in France.

Late in September 1918, during the heavy fighting in the Meuse-Argonne offensive, Lt. Rothman had established a dressing station to treat the wounded in Exermont. It was there that he was wounded and taken prisoner by German forces. At one point, reports listed him in a hospital at Treves (Trier), and later as being held at different POW camps, specifically those for officers. With the armistice in November 1918, Lt. Rothman and one other St. Louisan, Capt. Arthur H. Sewing, also of the Medical Reserve Corps, were released from the German POW camp at Villingen. They were two of the 51 officers and 22 enlisted men released from the camp that day.

Late in September 1918, during the heavy fighting in the Meuse-Argonne offensive, Lt. Rothman had established a dressing station to treat the wounded in Exermont. It was there that he was wounded and taken prisoner by German forces. At one point, reports listed him in a hospital at Treves (Trier), and later as being held at different POW camps, specifically those for officers. With the armistice in November 1918, Lt. Rothman and one other St. Louisan, Capt. Arthur H. Sewing, also of the Medical Reserve Corps, were released from the German POW camp at Villingen. They were two of the 51 officers and 22 enlisted men released from the camp that day.

For his service and actions in Exermont, Rothman was awarded the Silver Star. The citation reads:

“By direction of the President, under the provisions of the act of Congress approved July 9, 1918, 1st Lt. Henry L. Rothman, Med Corps, United States Army, is cited for gallantry in action and is entitled to wear a silver star on the Victory Medal ribbon as prescribed…For gallantry in action near Exermont, France, 29 September 1918, during the Meuse-Argonne offensive, in giving aid to the wounded under heavy enemy fire.”

After the war, now Capt. Rothman served in the US Health Service, and in July 1921 married Madeline Rocfort, a teacher at the Eliot School in St. Louis. Sadly, Henry L. Rothman died November 23, 1921 after a brief illness.

The photograph is taken from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 31, 1918.

July 5, 2017 – Maurice “Lefty” Jackman

Maurice “Lefty” Jackman lived a long, full life. Not something one would expect from a machine gunner and a mustard gas victim in the Great War. Maurice was born in 1895 to Philip and Anna (Annie) Jackman, Russian Jews, who immigrated to Providence, Rhode Island. Philip was a woolen merchant and soon moved the family to St. Louis where he founded P. Jackman & Sons.

In 1917, Maurice was drafted and joined the Marine Corps. “Lefty” was a machine gunner in France (March 1918-June 1919) and his regiment saw action in almost every major battle from Chateau-Thierry to the Meuse-Argonne. Late in the war, however, young Jackman was injured in a mustard gas attack and spent two months in the hospital.

At the time being a machine gunner was something new in the US military. Although machine guns had been around since the 19th century, they were hand-cranked and extremely heavy. They were still heavy at the beginning of WWI – and took a crew of four to six men to handle them – but now they were automatic. That made them the fearsome and deadly weapon most associate with the war. Throughout the war machine guns were re-designed to be lighter, thus they became offensive as well as defensive weapons and could be used on tanks, airplanes, and ships.

At the time being a machine gunner was something new in the US military. Although machine guns had been around since the 19th century, they were hand-cranked and extremely heavy. They were still heavy at the beginning of WWI – and took a crew of four to six men to handle them – but now they were automatic. That made them the fearsome and deadly weapon most associate with the war. Throughout the war machine guns were re-designed to be lighter, thus they became offensive as well as defensive weapons and could be used on tanks, airplanes, and ships.

Maurice Jackman had met his future wife, Frances, before he went overseas. “I told her we’d get married when I got back and we did” he once said. After the war, he also returned to his father’s business, where he later became president. The war, mustard gas, and the fighting did not slow “Lefty” down. He had played semi-pro baseball and handball when he was young, and he continued his love of sports after the war – even founding the Meadowbrook Country Club in Ballwin, Missouri. At age 82, he was still active, playing squash, hiking with the Catspaw Walking Club and golfing at the Triple A Club. In 1979, he even became a TV celebrity of sorts when he became a two-day winner on the Hollywood Squares game show. He died in 1985.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

June 28, 2017 – Samuel Goldberg

Samuel, known to most as Sammy, Goldberg was born in London around 1898 to Anna and Harry Goldberg. Sammy, his Russian parents, and a brother and sister who were both born in Africa immigrated to the US in 1904. Harry was a baker in the Biddle neighborhood in which the family lived, and Sammy attended Franklin School. At the young age of 16, Sammy enlisted in the 1st Missouri Infantry and served on the Mexican border in 1916 as an orderly to Colonel Donnelly. When the US entered WWI, Sammy and many others found themselves in a different conflict, this time in Europe.

Sammy became a well-known military hero for single-handedly capturing 18 German prisoners in September of 1918; he won the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions. General Pershing himself awarded young Goldberg his medal in April 1919, at Chaumont, France.

The citation read:

“For extraordinary heroism in action near Cheppy, France, September 26, 1918. When, under heavy enemy barrage and in the face of intense machine gun fire from both flanks and front at 150 meters (about 500 feet), the regimental headquarters and attached elements made a stand in front of the enemy line at Cheppy, Private Goldberg, a mere boy, acting as orderly for the regimental commander, displayed extraordinary heroism and initiative being always first to volunteer of a different task.

In utter disregard of his own safety, he dressed an officer’s wounds, exposed to intense machine-gun fire. When, after three hours, the assault was made, with the aid of tanks, upon the enemy position, Private Goldberg, having taking possession of a wounded officer’s pistol, armed only with this weapon, entered an enemy dugout alone and, at the point of the pistol, compelled 18 Germans to surrender, marching them back and turning them over to an officer. Later, when the action was over, guarding four German prisoners whom he impressed into service as litter bearers, he conducted a wounded officer, through a shell-swept area, back to a dressing station several kilometers to the rear. Private Goldberg displayed constant gallantry and heroism, and exhibited an inspiring example to his comrades.”

Not long after now-Sergeant Goldberg returned home to St. Louis late in 1919, he and 88 other Jewish WWI soldiers marched in protest against the pogroms in Russia and Ukraine. At some time in the early 1920s, he moved to Lexington, Kentucky, where he went into business and married Esther Rosenberg in 1924. Sgt. Goldberg was not forgotten, however, by the Jewish community or the City of St. Louis. During the construction of Roosevelt High School in March 1923, Sammy Goldberg was asked to add a something to the time capsule. Within the little box he placed a small American flag inscribed, “Sammy Goldberg, D.S.C.”

Photo appeared in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 1919.

June 21, 2017 – Lester Klauber

Slender, blue-eyed Lester Klauber enlisted in the US military in October 1917. At that time he was manager of the St. Louis Belting and Supply Co. on South 4th Street. Upon enlistment, Klauber became part of a new component in military warfare. He was part of Company A of the 1st Gas Regiment. Chemical warfare, while not unknown in earlier wars, became a common part of the Great War.

The French first used tear gas in 1914, but it was the later uses of chlorine, phosgene and mustard gases that left a real mark on international warfare. Chlorine gas was a powerful irritant and an effective psychological weapon. The green clouds of this more easily detected gas meant that you could see, and smell, it coming. At the time, soldiers in training were often told that it only took four unprotected breaths for chlorine gas to kill them. Phosgene gas was a colorless gas, often mixed with chlorine gas (known as “White Star”), and more difficult to detect. The effects of this chemical could take more than 24 hours to manifest.

By far the worst was mustard gas that was introduced in 1917. It was an effective disabling agent that not only caused enormous fear among the soldiers, but also contaminated everything and could stay active for months depending on the weather. Mustard gas, like many of the others used during the Great War, could cause blindness, and it also created large, ghastly blisters on skin. All of these gases affected ones lungs, often causing those exposed to them to feel as if they were suffocating.

Interestingly, gas was not necessarily meant to kill opposing soldiers. The creation of “gas shock,” an equivalent to “shell shock,” was equally effective on removing men from the field of battle as was the typical six to eight week recuperation period for those exposed to these chemical agents. The killing capacity of chemical warfare during WWI is considered “limited” in comparison to other methods, even though it is estimated that there were 90,000 combatant gas fatalities. Depending on the direction of the wind, all these gases also affected civilians in nearby towns and villages, not to mention poisoning the soil onto which it settled. Civilian casualties are estimated at between 100,000 and 260,000.

By the time the US entered the war, it had already mobilized various sectors to work on the research and development of poison gases. One major research center was established at Camp American University in Washington, D.C., and the First Gas Regiment was recruited specifically to handle the new chemical weapons that were developed, especially phosgene. Lester Klauber was one of the lucky ones. He was one of only three of the original 30 who enlisted in the gas service from St. Louis to survive the war.

The image is “Gassed” by John Singer Sargent, ca. March 1919, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

June 14, 2017 – Elkan Voorsanger

Elkan Voorsanger’s association with St. Louis was relatively short-lived, but his impact on the greater Jewish community and the military was long lasting. His relationship with St. Louis began in 1915 when he became the Associate Rabbi at Shaare Emeth under Rabbi Sale, after having graduated from the University of Cincinnati in 1913 and being ordained at Hebrew Union College the next year.

Like so many who wanted to serve their country, Rabbi Voorsanger resigned his position at Shaare Emeth in 1917, and in May of that year joined Base Hospital 21, a Red Cross-organized medical unit and found himself in Rouen, France. But things changed for Elkan Voorsanger in November of that year when Congress passed a bill ordering the appointment of chaplains of religions not represented in the military at that time. Rabbi Voorsanger was commissioned as a US Army chaplain on November 24, 1917 and became the first Jewish chaplain.

Like so many who wanted to serve their country, Rabbi Voorsanger resigned his position at Shaare Emeth in 1917, and in May of that year joined Base Hospital 21, a Red Cross-organized medical unit and found himself in Rouen, France. But things changed for Elkan Voorsanger in November of that year when Congress passed a bill ordering the appointment of chaplains of religions not represented in the military at that time. Rabbi Voorsanger was commissioned as a US Army chaplain on November 24, 1917 and became the first Jewish chaplain.

He was first assigned to the 41st Division in January of 1918, then a couple months later to Base Hospital 101 at St. Nazaire. It was there that Chaplain Voorsanger conducted the first official Jewish service (Passover) held in the American Expeditionary Force. In May, he was assigned to the 77th Division and became the senior chaplain (with the rank of Captain), directing chaplains of other faiths, all of whom provided whatever service and comfort they could to all soldiers of the Division. It was during his service with the 77th, during the battles of the Argonne (where he was wounded), Marne, and Chateau-Thierry, that Rabbi Voorsanger became known as the “Fighting Rabbi.” If his men went over the top of the trenches to fight, so did he. Because of his exceptional courage and devotion to duty in the time of danger, he received the Croix de Guerre and was recommended for Distinguished Service Medal.

Elkan Voorsanger stayed in France as a chaplain until April 1919 when he resigned his commission, but his work in Europe did not end. For the next six months he served as the Overseas Director of the Jewish Welfare Board. Then not long after he returned to the US that fall, he was once again asked to serve in Europe, this time as a commissioner with the Joint Distribution Commission in Poland.

The photograph of Elkan Voorsanger is courtesy of the Library of Congress.

June 7, 2017 – Julius and Maurice Razovsky

Julius A. Razovsky was the third of seven children born to Lithuanian immigrants Jonas and Minnie Razovsky. Julius graduated from the Benton College School of Law and was a medical student when he enlisted in August 1918 as a private in the Air Service. He was assigned to the Aerial Photography School in Rochester, NY, where the quick development of film was one of the primary skills taught. His younger brother Maurice, known to everyone as Maurie, also served in the war. Maurie was inducted as a private about two months later and assigned to the Mechanical School in St. Paul, Minnesota. At the time both men entered the service the family lived at 1026 N. 14th Street in St. Louis.

Although Julius was serving in the military, his name appeared on the ballot November 5, 1918 as the Republican State Representative candidate for the Third District in St. Louis. The night before election day, the St. Louis Post Dispatch reported that Julius Razovsky was scheduled to sail for France shortly and would most likely not be able to take office in January. Nevertheless, Julius Razovsky won the election. When he was released from service December 17, 1918, he took up his seat in the Missouri legislature.

The Razovsky brothers’ oldest sister, Cecelia, was also politically active in the early 20th century. She was a suffragist and a prominent social worker, employed by the St. Louis Board of Education and later with the National Council of Jewish Women, where she worked with the department of immigrant aid. In 1926, she worked with the federal Child Labor Division of the Children’s Bureau.

Julius married Minnie Blum after the war and kept a law office on North Broadway. He died in 1973 and is buried at B’nai Amoona Cemetery. Julius kept the Razovsky surname all his life, but Maurice later changed his name to Ross.

To learn more about the Razovsky brothers, or any Great War soldier from St Louis, go to: Genealogy.MOHistory.org/Genealogy/Names and type in a name.

May 24, 2017 – Base Hospital 21

More than nine months before the US officially entered WWI, the Red Cross called for the creation of a base hospital unit to be organized at Washington University St. Louis School of Medicine. Within a short amount of time, the entire faculty had volunteered for the unit. In fact, many members of the faculty had signed up for surgical units in France when the fighting began in Europe.

By the time of the US declaration of war in April 1917, the Red Cross had organized 33 base hospitals (eventually there would be 36), and within weeks they had selected six for immediate mobilization – including the one at Washington University. At the time, Base Hospital 21 had no commissions, no uniforms and no orders. The original 28 officers, 65 nurses and 185 enlisted men left St. Louis for New York on May 17 and arrived in Liverpool England on May 28, about a month after being mobilized.

Although Base Hospital 21 was a US unit, it was assigned to General Hospital 12 of the British Expeditionary Force and was assigned to take over the 1300-bed hospital at the racetrack in Rouen, France. The hospital was one of 14 British medical units established along the southern line in France in 1914. Not long after the Americans arrived, most of the British medical staff withdrew.

With the exception of the flu epidemic, Base Hospital 21 served as a medical clearing station. During the primary 18 months of its operation, the small staff of doctors, nurses and enlisted men handled more than 60,000 patients. Of that number, less than 5 percent (2,833) were Americans soldiers; the rest were British.

After the armistice, Base Hospital 21 continued their work but now cared for sick and repatriated POWs. The last patients left Rouen in January 1919 and the unit began to demobilize. Many of those who served with Base Hospital 21 were from the St. Louis Jewish community. Some were nurses, others were doctors, and still others enlisted men. Among those known to have served with the unit in France were:

Mae Auerbach

Olive Handy George

Isidore Goldman

Flora Kober

Edwin S. Kohn

Shepherd J. (Joe) Magidson

Nathaniel Saenger

Sidney Isaac Schwab

Julius V. Silberberg

Elkan C. Voorsanger

The photograph of Base Hospital 21 is provided by Becker Medical Library, Washington University School of Medicine.

May 17, 2017 – Jewish Welfare Board

On April 9, 1917 the Jewish Welfare Board (JWB) came into being to meet the needs of Jewish soldiers and sailors. Created by merging about a dozen national Jewish organizations, its goals were to meet the needs of Jewish soldiers. By September of that year, the JWB became one of the “Seven Sisters” of the United War Work Campaign. Although one of the five religious groups under that umbrella, the JWB did not want to segregate Jewish men and women from others, but rather to help “Jewish boys adjust themselves to understand and sympathize with their Gentile brothers-in-arms and to be, in turn, understood by them.” [New York Tribune 11/10/18]

Among the tasks undertaken by the JWB was the recruitment and training of rabbis for military service as chaplains and their oversight of Jewish chapel facilities at military bases. The JWB also sought to help with the recreational and spiritual needs of all soldiers at military camps, by providing them with religious services, prayer books, literature and music, as well as classes, concerts, lectures and debates. They also arranged to sell non-perishable kosher food in camps where Jewish soldiers were stationed.

Among the tasks undertaken by the JWB was the recruitment and training of rabbis for military service as chaplains and their oversight of Jewish chapel facilities at military bases. The JWB also sought to help with the recreational and spiritual needs of all soldiers at military camps, by providing them with religious services, prayer books, literature and music, as well as classes, concerts, lectures and debates. They also arranged to sell non-perishable kosher food in camps where Jewish soldiers were stationed.

The Board also organized branches in more than 150 US cities where community centers could help send off draftees, collect and distribute gifts, provide entertainment, help look after relatives left at home (especially in terms of correspondence), and offer hospitality when soldiers were on leave. Thousands of volunteers manned these centers throughout the US during the war. In time, there was even a JWB center overseas, headquartered in Paris for those serving in Europe.

In all, the Jewish Welfare Board provided about 50 Jewish chaplains during the war and served more than a quarter million Jewish soldiers. The centers and spiritual help were not restricted to Jewish soldiers. In fact, the idea was to show that Jewish beliefs did not conflict with what all soldiers were fighting for. The JWB noted in its own October 1918 publication that it “…sought to mobilize the enthusiasm and patriotism of the Jews of this country, and to muster the natural resources and forces of American Jewry…”

The photograph of the Jewish Welfare Board is provided by the St. Louis Jewish Community Archives.

May 10, 2017 – Rose Tuholske Jonas

Many people don’t realize today that not everyone wanted the US to join in the war effort in WWI. In fact, between 1901 and 1914 there were 45 new peace organizations that arose in the United States, most with the support of religious organizations, statesmen, politicians, and educators. The most ardent devotees, however, were women. Rose Tuholske Jonas was one of those women. The daughter of Herman Tuholske, one of the most prominent physicians in St. Louis and a founder of the Jewish Hospital, Rose was a charter member of the Women’s International League for Peace & Freedom (originally Women’s Peace Party) founded by Jane Addams in 1915. During her life, Rose was a member of the Jewish Peace Fellowship, the National Council for the Prevention of War, chair of the first peace committee of the National Council of Jewish Women, and a board member of the St. Louis Civil Liberties Committee.

Those who joined peace organizations did so for various reasons, and while many dropped their support of such groups after the US entry into the war, others like Rose did not. Rose Jonas’s German-born husband, Ernst Jonas, was a well-respected physician at the Jewish Hospital but not yet an American citizen when the US entered the war. Thus, he had to register as an enemy alien, one of 122 individuals in St. Louis who received the mandatory permit forms in May 1917. As a registered enemy alien, he was required to carry the permit as a pass that restricted him to certain zones of where he worked and lived. In 1918, Ernst Jonas was forced to resign his position at the Jewish Hospital because former staff members then serving in the military protested his enemy alien status.